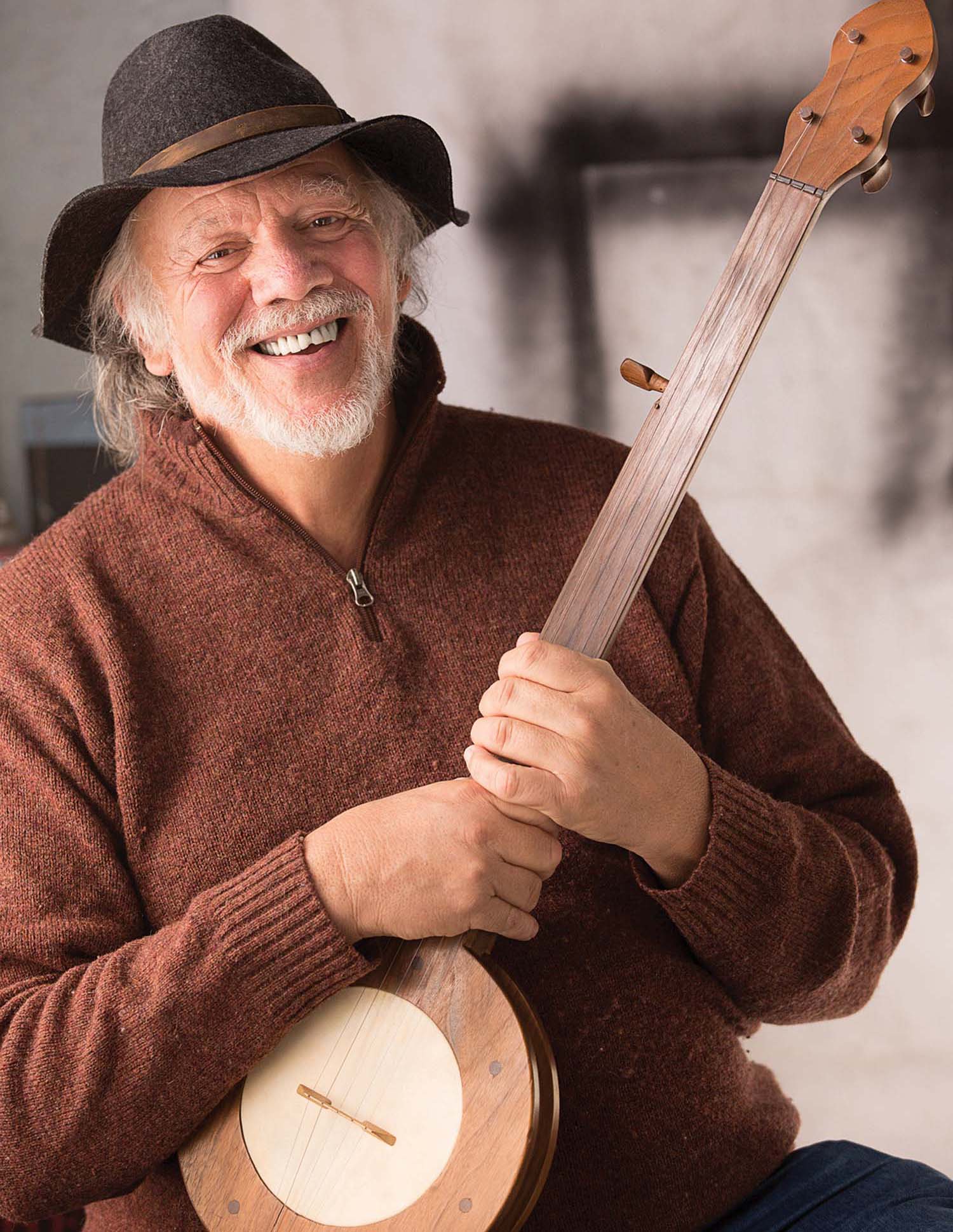

Lee Knight promises that the old ballads will never die out.

Lee Knight isn’t a direct heir of the late Lomaxes — John and his son Alan, whose ethnomusicology prompted the folk revival beginning in the 1950s — but his extensive field recordings certainly put him in the same territory. A “songcatcher” years before the term was trendily applied, Knight was raised in New York State’s Adirondack mountains, came south to go to Wofford College in Spartanburg, SC, and has lived for years in Western North Carolina, currently residing in Cullowhee.

He’s more apt to talk about the similarities in the two mountain traditions — both include “Child Ballads,” a 400-year-old, 300-plus collection of songs brought to the new world from the British Isles. The difference is the instrumentation. “There was more musical [accompaniment] in the Southern mountains — banjo, fiddle, guitar, Appalachian dulcimer,” he says. “The main instrument in the Adirondacks was the fiddle, [but] Adirondackers did not sing with the fiddle very often.” The fiddle drove the song, he explains, but the lyrics were sung a capella.

Knight’s multi-instrumental prowess proves his long stint in the South. When he’s not guiding whitewater rafters down the Nantahala, he’s playing one of ten or more traditional instruments, including the various banjo types that distinguish one Southern folk genre from the other. He travels the world teaching workshops, giving concerts, and continuing to add to his song collection celebrating ancient oral tradition.

“My fieldwork has been haphazard, based on opportunity,” he says. “So there was no plan, just whatever happened. I am sure academic folklorists must cringe at people like me.” But his curiosity certainly shaped his enormous range. Knight has collected songs in Scotland, the Soviet Union, and from the Gullah families of Johns Island near Charleston, SC. He plays with a world-music collective led by the Chinese pipa player Wu Man, a founding member of Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk-Road Collective.

But Knight started his career close to home, reaching out to people in the Adirondacks who had made field recordings, including Lawrence Older. Then he wrote to Frank Proffitt, a native of Beech Mountain in North Carolin’s high country who “gave” the local murder ballad “Tom Dooley” to Alan Lomax (it later became a hit for the Kingston Trio). “I got a letter back from his son, Frank Jr., telling me his father had passed on, but he would be glad to meet with me,” Knight recalls. “That started a long friendship, and through him, I met his uncle, Ray Hicks, a wonderful storyteller.”

Such personal connections fretted his career. Marjorie Lansing Porter, an early historian whose reel-to-reel recordings in the Lake Champlain region provided material for the famous Seeger family, asked Knight to organize her work and get it into print. “I am one of the luckiest people in the world,” he says.

Not that the journey’s always been smooth. Knight was picked to appear in the 2000 movie Songcatcher, filmed near Asheville. “I was hired to be the hands of the actor playing the banjo,” he says. “Sadly, my brother-in-law was killed and my sister was injured in a plane crash the week my hands were going to be filmed.

“I do believe that things are cyclical in our lifetimes,” he adds. “In both music and movies, we seem to go back and forth between high-tech and simplicity. People have been saying for many years that the old songs and ballads will die out. I don’t think so.”

“From a Songcatcher’s Notebook,” featuring Lee Knight, happens at Kaplan Auditorium at Henderson County Public Library (301 N. Washington St.) Wednesday, March 14, at 5:30pm. Free. For more information, call 828-693-7757 or see leeknightmusic.com.