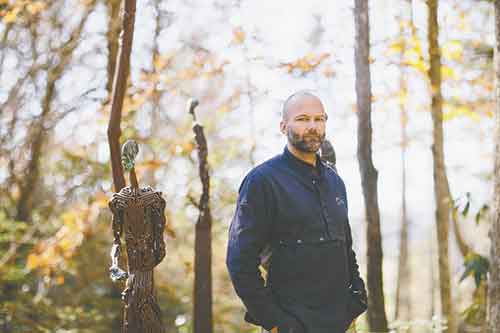

Photo by Tim Robison |

Works made from steel and copper take strength. Notions of delicacy or tenderness do not come to mind. Yet “delicate” and “tender” are words frequently used to describe the sculptures of J. Aaron Alderman, a Brevard native whose unique style owes much to the two-dimensional element of line.”I feel like what I am doing is drawing,” he says. “I still draw.” After completing studies at Brevard College and receiving training from metalworkers Tim Murray and J.T. Cooper, Alderman began creating both animal and human forms “to capture a tender, emotional expression.”

His method of bending thick steel rods to sculpt a form is well recognized from his work with the Brevard Sculpture Project, which highlights 16 indigenous animals, their forms scattered around downtown Brevard. Alderman’s contributions include his life-size cows: a mother with two calves is located on King Street, in the artsy Lumber Arts District. His tight, controlled use of line crafts the three-dimensional forms, also including elk and turkey.

This similar rigid line is seen in the piece “Sweet, Lost & Found, and Pathos,” a set of three sculptures that feature human forms from the waist up, set on contrasting angled pedestals. The figures are faceless, although the musculature created by the line and the gesture of the arms implies drama. The green copper hands also provide a striking contrast to the warm rust color of the steel.

“I am not here”

|

This is a common sight in Alderman’s figurative human works: green copper hands that are wiry, withered; some have even said “tortured.” The hands are large, likewise the feet, a conscious nod to Rodin.The hands capture Alderman’s intention. To explain, he paraphrases Great Expectations: “People always tell you that the eyes are the windows to the soul. Bullsh**. It’s your hands. Hands are the sign of a true gentleman.”

Alderman welcomes the ambiguity of hands as opposed to eyes, which provides rich fodder for art-making.

Though the hands are a consistent sight, a shift in his style embraces a loosening of his linework into more organic forms. “I’m highly influenced by Jackson Pollock and Egon Schiele,” he says, “and what they could accomplish with line.”

This is evident with works like “Karma Police,” a strong figure with an extremely foreshortened head that seems to be floating away. Hands reach up to grab the head, but are unable to do so. The piece is named after a song by the band Radiohead. The lyric “For a minute there, I lost myself” is repeated over and over. “That’s what the sculpture is all about: losing yourself, for good or bad,” says Alderman.A new set of three sculptures, as yet untitled, mimic “Karma Police” in their organic, twisting lines, as well as in the copper heads, dwarfed by the pieces’ large hands and feet. These works are smaller in scale than many, only 3/4 size, though Alderman asserts the approachability of these works for the viewer — as opposed to some others that tower 12 feet or taller.

The disproportionate feet-to-head ratio references the work of sculptor Alberto Giacometti and also reflects Alderman’s own observations: “I wanted to create pieces that show in 3D form how a human shadow is cast along the ground,” he says.

These new works are likely to be found soon at Haen Gallery in Brevard, which has represented him since spring of 2014.

“Absence of a Dream” features three human forms with large 3D feet; tall thin legs; and 2D, simplified, armless torsos. The figures are gangly, inverted. Combined with the title, the implication is of a missing companion. Alderman also explores alternate materials of cast plaster in “Forget the Man: Remember the Sin.” Using more direct visual references to Jesus Christ, two outstretched hands, cut off at the wrists, are held to the wall by metal spikes. A crown of thorns hangs in the air, dramatically lit between the hands.

The torso we expect is missing: the resulting empty space is powerful.

Though his subject matter isn’t always so direct, Alderman references spirituality in his process. “Sometimes art can seem incredibly selfish,” he states; he feels driven to create art that is “ego-less,” despite the obvious element of self-portraiture in his human pieces.

“Some Hindus believe that artists need not meditate as much as others, because their art-making is itself meditation,” he concludes.

J. Aaron Alderman is represented by the Haen Gallery, Thehaengallery.com. See more of his work at Volumesofsteel.com.