Merchant Marine tells war stories and educates visit

By Jarrett Van Meter

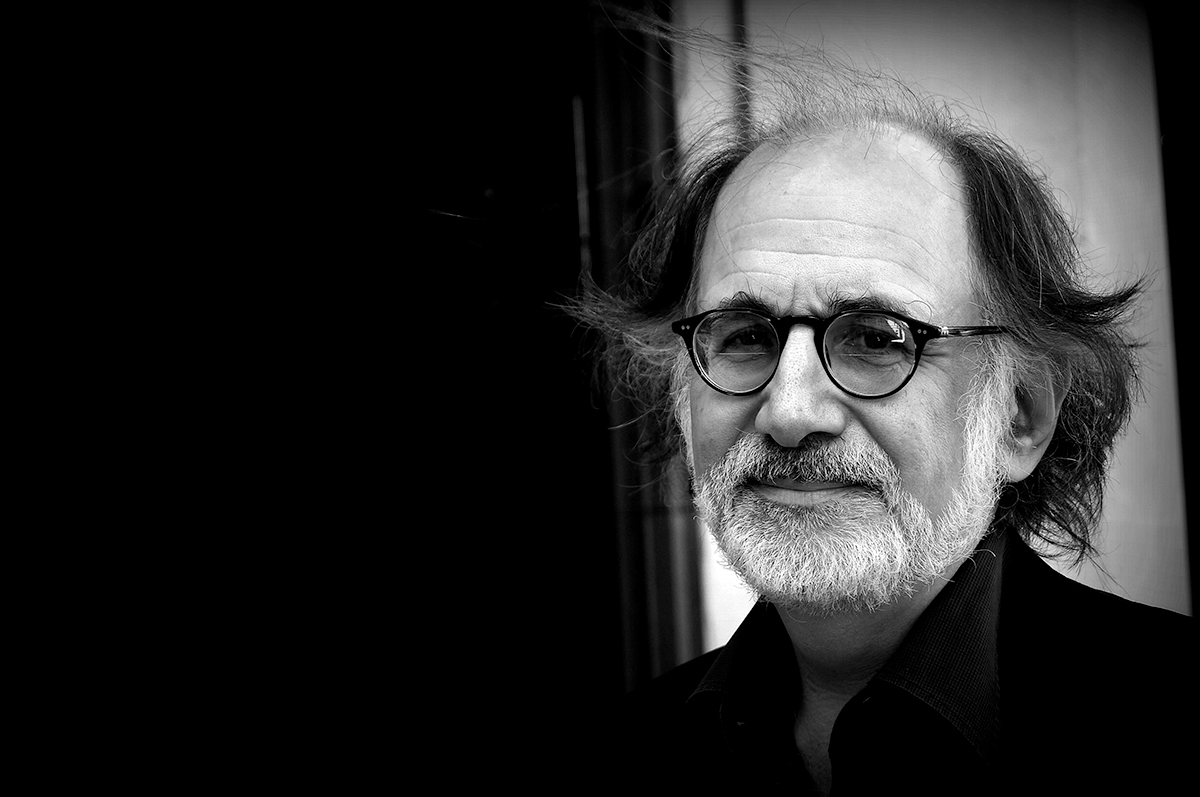

Retired Merchant Marine Harold Wellington loves to answer questions at the Veterans History Museum of the Carolinas in Brevard.

Photo by Karin Strickland

His bags were packed and he waited for the call. In March of 2020, Harold Wellington was ready to drive to Washington DC to be on hand for the authorization of the Congressional Gold Medal for American Merchant Mariners who served in World War II, approved the year before in a bipartisan bill. It was set to be a moment of long-overdue recognition for a group that suffered a higher percentage of deaths in WWII than either the Army or the Navy.

Then the pandemic erupted. While the legislation was still signed, the moment was relegated to quiet obscurity, much like the Merchant Marine itself.

A LIFE AT SEA

In this vintage photo, Harold Wellington is seen in the front row in dark swim trunks (#3 hatch behind the wheelhouse on the Edmund Fanning Liberty Ship en route to London).

Photo by Karin Strickland

While technically not a branch of the military, Merchant Mariners — who operate every kind of watercraft, from river cruise boats to dredging vessels to deep-sea warships, transporting cargo and people between countries in peace and in wartime — have faced perils equal in magnitude to their enlisted peers. Industry stresses include isolation onboard, long periods of time separated from family, chemical exposure from hazardous materials, and the threat of modern-day piracy.

As an auxiliary to the U.S. Navy, Merchant Mariners move military personnel and supplies in high-conflict waters. As John McPhee wrote in his 1990 book Looking for a Ship, “In time of war, the Merchant Marine is a prominent participant. This civilian job — risky enough at any time — becomes exceptionally dangerous.”

UNIFORM DECISION

In 1988, the Merchant Marines were finally granted veteran status.

Photo by Karin Strickland

There are not many WWII Merchant Mariners left. Wellington, who is 96 and lives in Brevard, has compiled many of his own relics into a new, permanent display at the local Veterans History Museum of the Carolinas.

“I hope people come away and realize what we did, and we got nothing,” he says. “I wouldn’t even admit I was a Merchant Marine when I came home, because people would say, ‘You’re nothing but a drunken draft dodger!’ Ninety percent of the people in the Merchant Marine were there because they wanted to be, because there was no draft to be put in the Merchant Marine. It was all volunteers, and the biggest share of them were guys who couldn’t get in the military.”

Navigation sextant from a lifeboat.

Photo by Karin Strickland

Since it was a civilian job, those turned away by the Army, Navy, and Marines could join the Merchant Marine. It was an opportunity to serve, travel, and earn a paycheck at sea.

“The Merchant Marine didn’t care if you had flat feet or were colorblind … [if] the service wouldn’t take you, the guys would go down and join the Merchant Marine —guys from 15 up into their 70s.”

Wellington originally intended to join the Navy, but was turned away by the recruiter in his hometown of Windsor, Vermont; he was told that the Navy already had so many men that they couldn’t take him.

Wall-mounted maritime clock from a ship.

Photo by Karin Strickland

“The Navy recruiter told me to go down the hall,” Wellington remembers. “He said there was a Merchant Marine recruiter down there and that they were begging for men.”

Thus began the adventure of a lifetime. After training in Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, Wellington landed a job on a Liberty ship. Over the next few years the job took him to Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America. Despite being a civilian job with none of the perks of military status, Merchant Mariners often found themselves in the throes of combat. Franklin D. Roosevelt was an advocate for the Merchant Marine and was pushing for the group to receive veteran status and benefits before his death in 1945. But members of the Merchant Marine were left on the outside looking in until 1988, when Wellington and his fellow Merchant Mariners were granted veteran status, giving them access to VA hospitals.

“We were right there manning those guns and everything right there beside the Navy armed guard crew,” says Wellington. “We were always trying to dodge air raids in the Mediterranean and submarines in the north Atlantic.”

Photo grouping of buddies on a Liberty ship and life vest from a WWII tanker.

Photo by Karin Strickland

The local display contains photos, a model replica of a Liberty ship, and the uniforms that trainees had to wear prior to serving on a particular ship. The item Wellington is proudest of is the medal of appreciation he received a few years ago from the Convoy Cup Foundation in Norway. He says he hopes exhibit guests gain an appreciation of the unheralded group and an understanding of what it was that they did.

“Nobody else had any cargo ships to carry [war materials],” he says. “We had to deliver all this stuff to Europe, South Pacific, wherever the war was.”

Wellington occasionally leads tours of the exhibit, filling in the space around his descriptions of the displayed items with stories.

“I enjoy trying to educate the people. A lot of people don’t even know what Merchant Marine is and what they did.”

Veterans History Museum of the Carolinas, 21 East Main St., Brevard, open Wednesdays through Saturdays, 11am-3pm. For more information, including tours of the Merchant Marine exhibit by appointment, call 828-884-2141 or see theveteransmuseum.org.