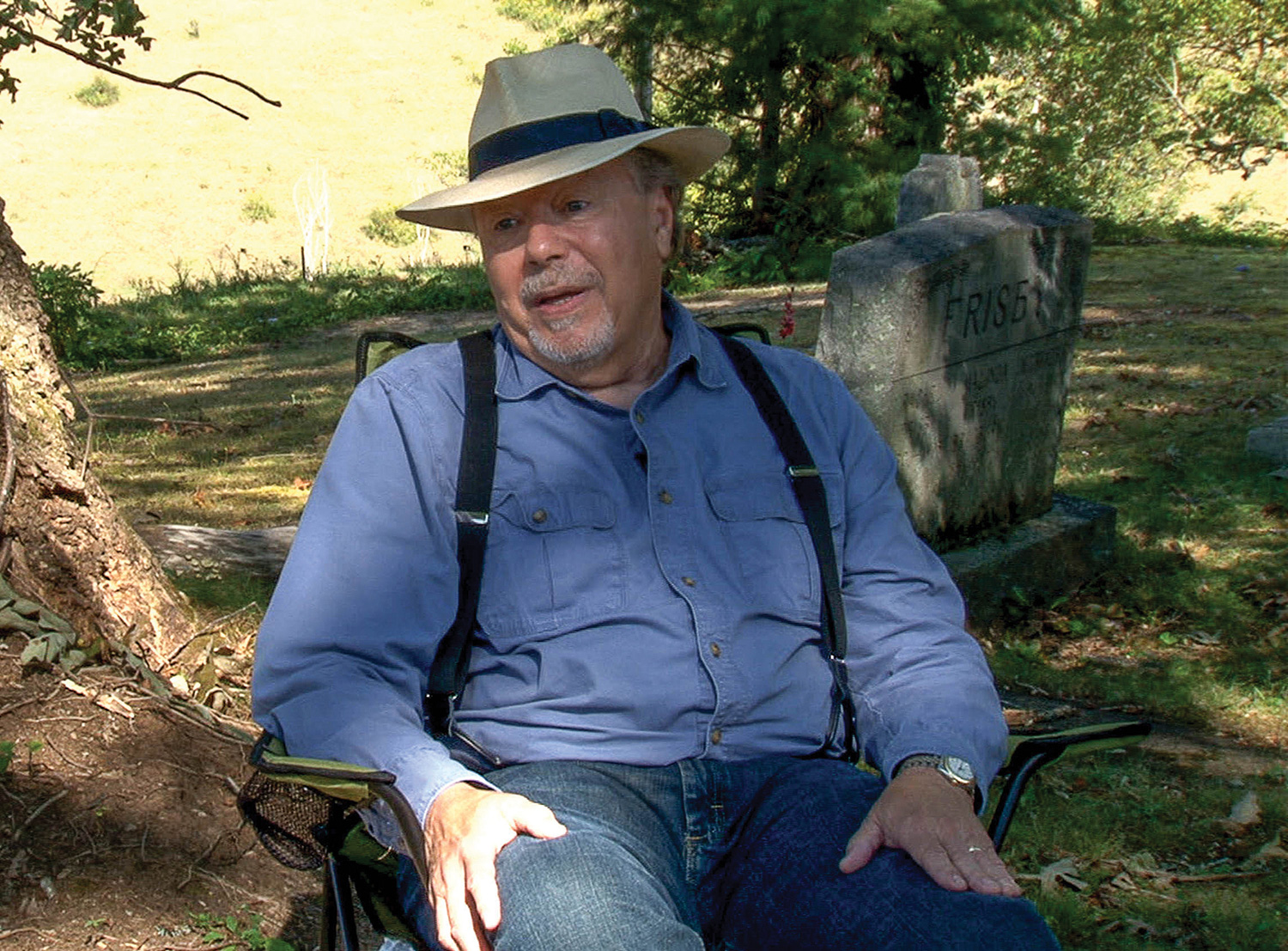

“The important part is that the story be told,” says Joe Penland, whose work in the old-time ballad tradition makes him an important figure in mountain music.

“I didn’t know I was a storyteller until I was told I was one,” says Joe Penland. A singer, songwriter, and most definitely a storyteller, Penland, who grew up in Madison County, is part of the century-long movement to keep old-time love and murder ballads alive. A lyrical tradition that Appalachian settlers brought over from England and Scotland, the genre includes tunes dating back to the 1600s.

In 1916, British visitor Cecil Sharp became the first known “song collector,” choosing Madison County as his field of study and jump-starting the folk revival of the 20th century. Mountain-derived fiddle tunes and ballads (“Shady Grove,” “Wayfaring Stranger,” and hundreds of more obscure songs) can still be heard at traditional festivals across the country.

Penland, interviewed here, is one of the featured subjects in From Knee to Knee: The Roots of Mountain Music, a new film by David Weintraub and his Hendersonville-based Center for Cultural Preservation.

An oral tradition that’s some 300 to 400 years old means song content inevitably changes over time. What are the effects of those changes?

The stories are more condensed, usually, and more concise; extraneous material seems to be left out. But the essence of the stories remains, and can even be more clear. But with the folk process, it’s hard to say how that affects everything. I can’t tell you how the songs sounded two or three centuries ago. We only know how they were a hundred or so years ago, when they were collected by Dr. [Francis James] Child, or Cecil Sharp, who actually put the songs down [on paper].

Practitioners of old-time music and story-songs often talk about the importance of saving the traditions, as if they’re somehow in peril. Are these traditions truly threatened?

In their antique way, yes. These stories have been told over and over, and certainly will have changed over time. Who am I to say which is the more valid form of the song? Whether it’s delivered on the written page or sung by a singer accompanying himself, or even a cappella, the important part is that the story be told.

Do you think it’s important to keep them musically true to the way they were done generations ago, or is it permissible to tweak them to make them more accessible to contemporary audiences?

I don’t think anyone has asked permission. If you perform a song that I’ve written, you’ve sort of decided to make it your song. I find that acceptable, as long as people understand that I wrote the song to begin with. Any way that the stories are presented personally is okay; the story lives on.

What separates these folk songs from more formal kinds of music?

They were the songs of the common man. Even in the 18th and 19th centuries [in England and Scotland], folk songs were not the songs of nobility; these were the songs of peasant people. That was important to collectors like Child and Sharp.

Any revelations after sharing your thoughts in Weintraub’s film?

The more you talk about a thing, the more vibrant it becomes. David asked me to sit and talk about the ballad tradition, but I have no recollection of it, other than that he got me started. … Sometimes I feel that if you put too much conscious effort into recollection, you leave out the essence of it. When I [perform], I have an idea where I’m going, and memory can take me where I need to be.

From Knee to Knee: The Roots of Mountain Music will be shown at the Culture Vulture Film Festival, November 4 at the Blue Ridge Conference Hall (Blue Ridge Community College). Also: a screening of A Mighty Fine Memory (about master fiddler Roger Howell); the Popcorn Sutton documentary The Last One: Moonshine in Appalachia; student films; live music; BBQ; and a panel discussion featuring historians, ballad singers, and former moonshiners. 6pm for dinner, music, and films ($20); 7pm for just films ($15). 828-692-8062, saveculture.org