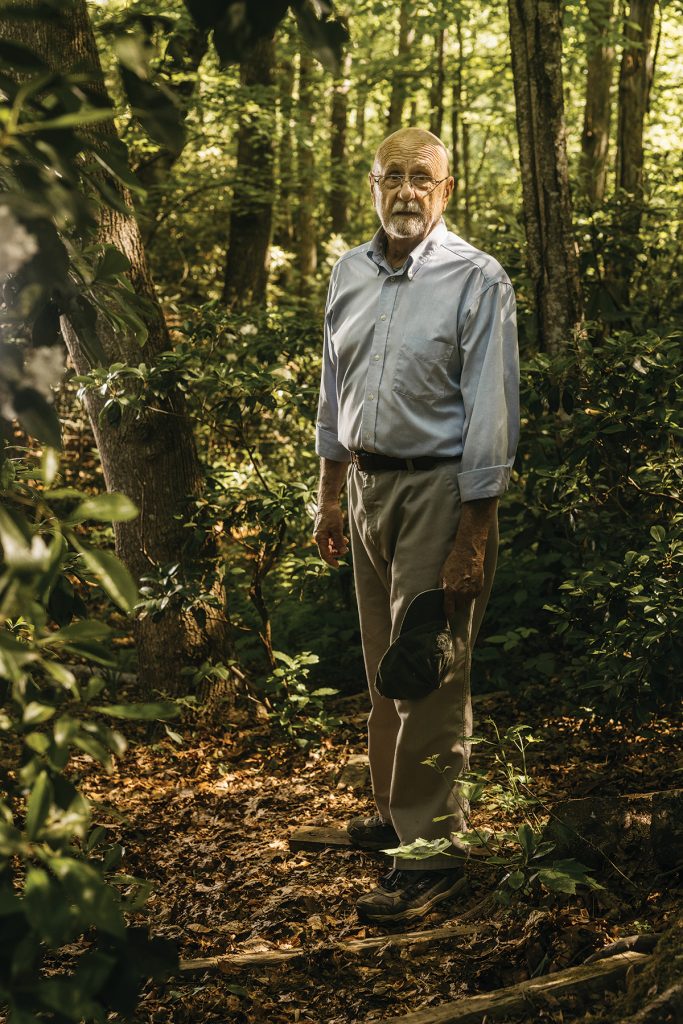

Retired biologist celebrates biodiversity in the backyard

ON GOLDEN POND

Retired conservation biologist Tom Baugh freed a hidden spring on his own property that acts as a watering hole for local animals and teems with biodiversity.

Photo by Evan Anderson

It’s too chilly for copperheads to be out. That’s the reassurance Tom Baugh offers as he picks his way down a steep, rhododendron-lined path in his Henderson County backyard earlier in the season, with temperatures way below normal. “They are our neighbors,” he says of the venomous reptiles, pointing to a granite outcropping where they like to sun themselves, now that it’s summer.

Copperheads are just part of the reason why Baugh, an 80-year-old conservation biologist with wireframe glasses and a salt-and-pepper mustache, is descending into the forest. When he and his wife, Penny (a punch-needle artist covered in the April issue of Bold Life) purchased the woodland lot 20 years ago, they unknowingly became stewards of what they now call Hidden Springs — a 25-foot-wide watering hole for bears, white-tailed deer, coyotes, foxes, bobcats, turkeys, and, as time would tell, snakes. “We had no clue it was here until we received our plat map and it mentioned a pond,” Baugh says of the oval-shaped pool.

Located at the lowest point in the front of Hidden Springs, the Bioswale channel slows run-off, leaving the yard and filter materials from entering the nearby stream.

Photo by Evan Anderson

Though Hidden Springs is less than 100 yards from the Baugh’s ranch-style home, it is well concealed by mountain bramble and, thus, aptly named. Just a glimpse of the spring requires scrambling down a dozen wooden steps that drop 70 feet into a hollow. The walk takes three minutes in earnest, though Baugh makes frequent stops to point out speckled wood lilies and Southern nodding trillium.

“This is rattlesnake plantain,” he says, tenderly pushing back debris to expose a squat plant with dark green leaves. “They’re actually a member of the orchid family but just aren’t showy.”

Morning dew

Photo by Evan Anderson

The walk goes on like that, with Baugh pausing to reel off knowledge about galax, a leathery-leaved plant prolific in Southern Appalachia, and the Apricot Surprise azalea, a deciduous plant that produces pinkish-orange blooms in the warmer months. Baugh planted most, if not all, of the property’s native flora.

However, he did have some help. “Ants are great transplanters,” he laughs, noting that the insects have carried trillium all the way to the neighbor’s yard. “Birds are, too.”

Ferns on the property

Photo by Evan Anderson

After a discussion about pollinators and a hairpin turn, Hidden Springs comes into view. Though it looks placid, a small pond fed by a seep, “this is habitat,” notes Baugh. It is here that four-legged creatures come to drink and that smaller critters like snapping turtles and wood frogs come to live. Though the water, in late spring, is covered in a film of pollen and samaras — the winged maple tree seeds commonly referred to as “helicopters” — appearance has little bearing on quality.

“One of the best indicators of water quality is the ecological community that it supports. If you have salamanders, frogs, and plants of various sorts, you probably have good water,” says Baugh, who worked in science communication with the U.S. Forest Service and as a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Department of the Interior before retiring in his sixties. After leaving the “daily grind,” Baugh volunteered at Bat Fork Bog Plant Conservation Preserve, a wetlands ecosystem in Henderson County that harbors several rare plant species including the Bunched Arrowhead, a herbaceous plant that produces edible tubers.

A pollinator box

Photo by Evan Anderson

Like Bat Fork Bog, Baugh’s backyard is a microcosm of biodiversity. “There’s no question that living here requires a constant association with other living things,” he says. “Part of the biodiversity has to do with the way the Appalachians developed, with mountains and valleys separating populations of animals. Those populations then evolved, or speciated, into different species.”

A close up of the mountain laurel

Photo by Evan Anderson

Salamanders are a great example of this evolutionary process. Since these lungless amphibians have a very small range, populations in the Southern Appalachians have evolved in relative isolation. As a result, this region supports the highest salamander diversity of any area on Earth. Baugh has identified a handful of species on his property, and this year’s project is to explore Hidden Springs in hopes of identifying even more salamander species. “It’s like the mountain that Edmund Hillary climbed — Everest,” Baugh says of the project. “He did it ‘because it was there.’”

In a way, Baugh also feels a certain obligation to the land. Last summer, for instance, he spent countless hours removing a toppled red oak from Hidden Springs using only hand tools— a huge feat, considering his age and the fact that he’s had two strokes.

Spring bloom

Photo by Evan Anderson

“Maybe, in a way, caring for and conserving this land is a celebration of me being 80,” Baugh says as he stands at the water’s edge. Chickadees and nuthatches chatter somewhere in the laurels and the wind rustles the canopy above. “But I also just love to play in the mud.”

For more information about Hidden Springs, contact Tom Baugh at hiddensprings2@gmail.com.

I am the lucky next door neighbor that gets the rare trillium seeds that the ants bring over from Tom’s garden. I also get the knowledge from Tom about a myriad of native flora and fauna. Thanks for such a vivid article on Tom Baugh and his wonderful Hidden Spring.