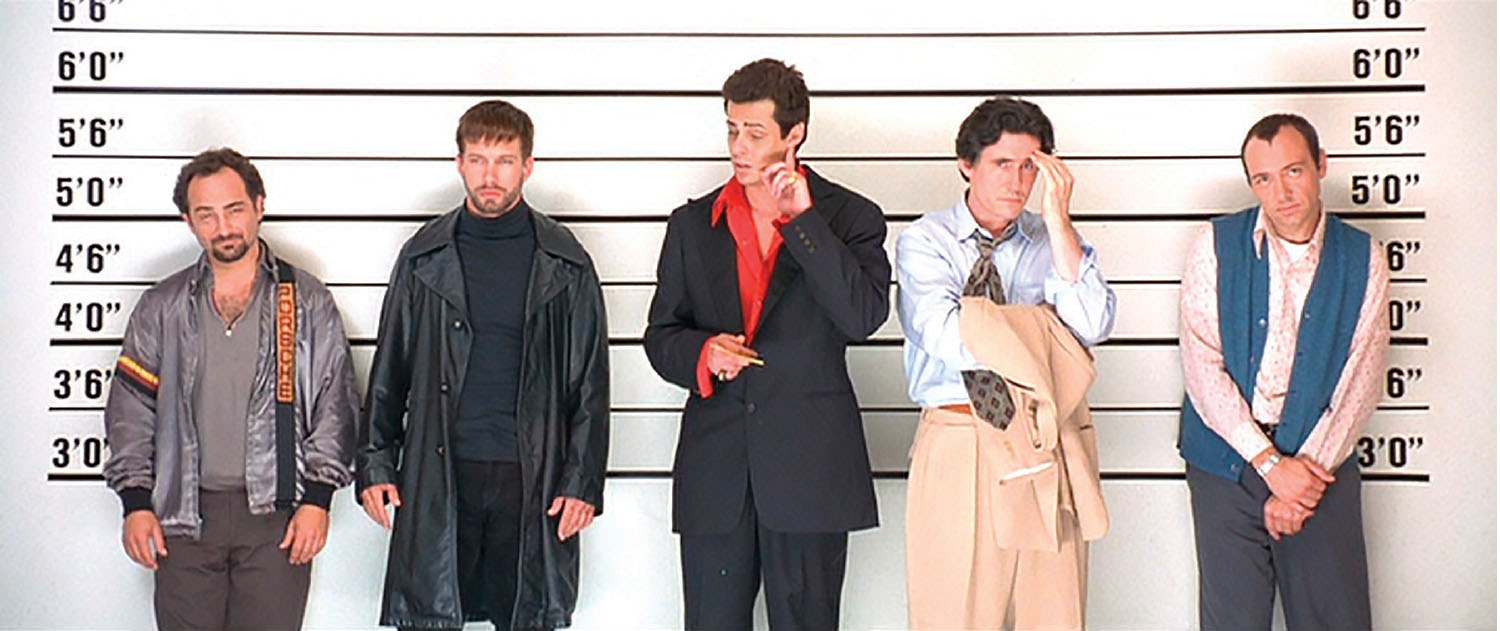

Five brilliant actors — Kevin Pollak, Stephen Baldwin, Benicio del Toro, Gabriel Byrne, and Kevin Spacey— are evil criminals in The Usual Suspects. It’s one of four films offered in a unique college course this fall.

The best movies are like dear friends. You visit often and ask different questions each time. Most follow the classic, linear, three-act structure taken from ancient Greek theater — beginning, middle, end. Unless they don’t. Consider what French New Wave filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard once said: “I agree a story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order.”

Ever since her grad-school days studying film at Boston University, Beth Ellers has been fascinated by nontraditional movies. First, she examines the script, which establishes the structure of the story on the page. Then, she analyzes the film aspect that’s most apparent to audiences — the way the story’s structure is visualized by editing. She’s designed a marvelous four-week film-appreciation course at Blue Ridge Community College Center for Lifelong Learning. Though the featured movies are very different from one another, an inventive use of plot unites them.

The Usual Suspects (1995, Rated R) is one of my all-time favorites; I’ve seen it 20 times at least. It’s a complex neo-noir crime tale, cutting back and forth from the present to various times in the past. It makes the audience come face to face with an evil so common we don’t usually notice it: telling lies.

The young filmmakers who created Suspects were wildly talented — and because their budget was so low, they often had to accept a quirky first result rather than spend time (which is money) to get the perfect take. The result is a work of exciting spontaneity.

The remarkable Oscar-winning script, mysterious and full of twists, was written by a former private detective, 27-year-old Christopher McQuarrie, who’s since come a long way (he’s writer/director of this summer’s Tom Cruise juggernaut Mission Impossible —Fallout). Usual Suspects’ director was McQuarrie’s friend, 30-year-old USC cinema-school graduate Bryan Singer, who went on to direct movies with stratospheric budgets, including X-Men Apocalypse (2016).

One of Singer’s USC classmates was John Ottman, a phenomenal dual talent who not only edited the intricate film but also wrote the original music. He performed the same roles on several of Singer’s blockbusters.

The behind-the-scenes magic was doubled onscreen. A thrilling cast brought to life violent criminals who were so human that audiences grew to care about them. Kevin Spacey won an Oscar for his breakout role as the weaselly small-time crook with cerebral palsy. He went on to a legendary career, abruptly derailed by recent scandals. Another actor, Benicio del Toro, mumbled so badly you could barely understand him, but audiences loved him so much he was able to turn his small part into a thriving career.

Amelie (2001, Rated R) is another gem. With 80 different locations set in enchanted Paris, it sparkles with endless charm as it careens between reality and fantasy. A sweet waitress in Montmartre (the marvelous 25-year-old Audrey Tautou) invents escapades to help unwary strangers, especially a kooky motorcyclist who does weird things with photo booths. Amazingly, director/co-writer Jean-Pierre Jeunet was self-taught, but his incredible talent won Amelie the Palme d’Or at Cannes and five Oscar nominations. (I reviewed the film in detail last year: boldlife.com/making-mischief/.)

The only film in the series I’d never seen before is the modern western Lone Star (1996, Rated R). Set in a distressingly realistic Texas border town, the story unfolds from the present to several different pasts, revealing painful secrets with each new discovery. Two of the characters are played by actors early in their careers, Chris Cooper and Matthew McConaughey. Directed/written by MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant winner John Sayles, the script was Oscar nominated. (Sayles also made the deeply magical The Secret of Roan Inish, 1994, which I wrote about a couple years ago: boldlife.com/scenery-is-a-crucial-character-in-beloved-magical-realism-film/.)

The course ends on a happy, feel-good note. Strictly Ballroom (1992, Rated PG), is a swirling Australian dance tale that never stops showing off its sequins, or its secrets. An ambitious young dancer (classically trained Paul Mercurio) struggles to bring excitement to staid ballroom dancing. The movie began life as a wildly popular stage production, directed by real-life ballroom dancer Baz Luhrmann, who insisted on directing the film version. He went on to direct/write more movies, including his most famous, Moulin Rouge (2001), and the controversial American film The Great Gatsby (2013), starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Ironically, the movie he got terrible reviews for, Australia, starring Nicole Kidman and Hugh Jackman, was one of my favorite movies in 2008.

The surprising benefit of movies with nontraditional story structures is you can see them more than once and they’re still compelling. “I see something different every time,” confirms Ellers. “I may know the ending after the first viewing — but the later viewings allow me to see all the clues I missed.”

It seems that seniors in particular like movies that play with time. And Ellers, who leads analytical discussions after each screening, enjoys teaching them. “They’re only taking the classes for fun,” she points out, “so they come because they want to — and they bring a lifetime of experience with their perspectives.”

Storytelling in Films, 4 sessions, Mondays, 1-4pm, October 15, 22, 29 and November 5. Room 122, Continuing Education Building at Blue Ridge Community College (180 West Campus Drive, Flat Rock). $50 BRCLL members (age 50+); $60 nonmembers. Call 828-694-1740 or email brcll@blueridge.edu to register. www.brcll.com.